In a recent clinical trial in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas, investigators from the Center for Neuro-Oncology at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center set out to test the safety and effectiveness of controlling the powerful immunotherapy human interleukin-12 (hIL-12) by using an oral activator to control when the gene gets turned on. While hIL-12 can stimulate many branches of the immune system, previous clinical trials that leveraged it were halted because of toxicity.

Results from this new multicenter phase 1 trial, led by Antonio Chiocca, MD, PhD, chair of the Brigham’s Department of Neurosurgery, and surgical director of the Center for Neuro-Oncology, are more promising: The drug-inducible gene therapy approach showed anti-tumor effects, with tolerable and reversible side effects. The study lays groundwork for more robust clinical trials of this therapy, with potential applications for glioblastoma and other disorders for which regulating gene expression might be desirable. Results were published in Science Translational Medicine.

“In a phase 1 trial, we’re always trying to find a glimmer: Is there any evidence of efficacy? These results give us that glimmer of hope,” said Chiocca, corresponding author of the multi-center study. “We believe it is now possible to do regulatable immunotherapy via genes. It’s well-tolerated in patients with glioblastoma, with some encouraging evidence that the drug is having its intended effect.”

The research team applied a two-part strategy to 31 patients with recurrent GBM, with the aim of minimizing systemic toxicity. At the time of surgery, patients received an injection of a vector (Ad-RTS-hIL-12) that delivered an IL-12 drug into the tumor resection cavity. The IL-12 gene had been altered to be inactive when injected, but to switch on in the presence of the oral activator veledimex. Before surgery, patients received a dose of veledimex. They continued taking the drug for 14 days after surgery.

Results showed that veledimex did cross the blood-brain barrier and switched on the IL-12 gene. Patients received 10-40 mg of veledimex, and the researchers reported dose-related increases of veledimex, IL-12 and other measures of immune activity in the blood of patients. Frequency and severity of adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome, correlated with the veledimex dose and reversed promptly upon discontinuation.

Patients taking the 20 mg dose of veledimex, which was determined to be the best tolerated dose, had a median overall survival rate of 12.7 months. The research team included collaborators from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Northwestern University, University of Chicago, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Ziopharm Oncology, Inc.

The researchers found that taking corticosteroids while on the IL-12 gene therapy negatively impacted survival. Prescribed to relieve brain swelling, corticosteroids are also immunosuppressive, which possibly dampened the effectiveness of the therapy. Overall, patients taking 20 mg of veledimex with minimal corticosteroids had a median overall survival of 17.8 months (6.4 months for those on corticosteroids).

While these median overall survival times are favorable compared to recurrent glioblastoma historical controls of 6 to 9 months reported in previous studies, advanced studies with more patients are needed to confirm whether the treatment is truly efficacious.

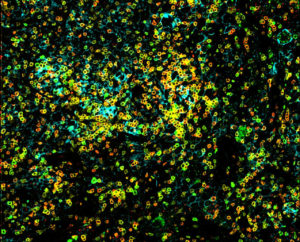

One encouraging sign is that when the investigators had access to tissue from tumors that had been treated with the IL-12 gene therapy, they saw evidence that immune cells had infiltrated the tumor, essentially turning the tumors from immunologic cold tumors into hot tumors. But they also saw evidence of increased checkpoint signaling, a trick that cancer cells use to stop the immune system. As a next step, the team is combining IL-12 gene therapy with intravenous checkpoint inhibitors. A phase 1 clinical trial is now underway.

“There is the potential to use this approach not just with IL-12 but for a variety of other genes that you might want to express and regulate,” Chiocca said in a recent interview. “You want to have the ability to turn them off and on as needed. This is drug-inducible gene therapy, which we have now tested and used for the first time in humans.”

The clinical trial and correlative studies were funded by Ziopharm Oncology, Inc. and by the National Institutes of Health.