Could understanding a patient’s personal network of friends and family provide important clues to health and illness, and even guide care? Neurologist Amar Dhand, MD, DPhil, of the Department of Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, is investigating the relationship of personal networks and stroke, with some surprising findings.

Could understanding a patient’s personal network of friends and family provide important clues to health and illness, and even guide care? Neurologist Amar Dhand, MD, DPhil, of the Department of Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, is investigating the relationship of personal networks and stroke, with some surprising findings.

It is known that approximately 70 percent of people in the U.S. who have a stroke arrive at the hospital more than six hours after symptom onset – potentially making the difference between a life-altering cerebrovascular event or one with excellent recovery due to early treatment.

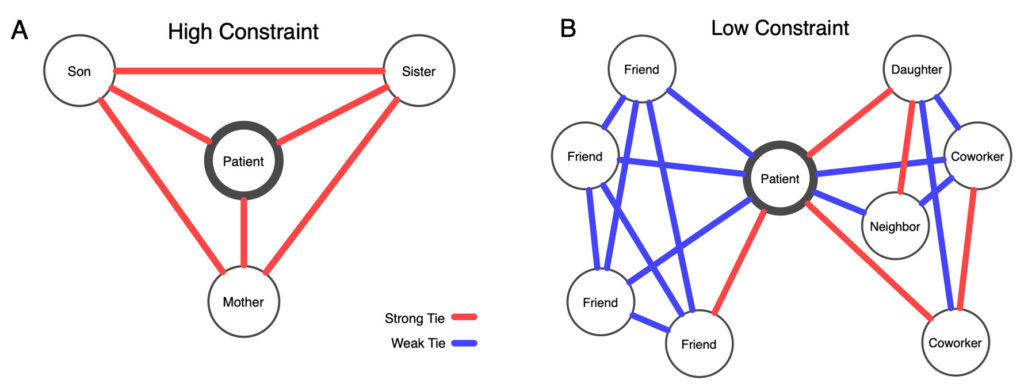

In a recent study, Dhand and colleagues found that patients who arrived later at the hospital with mild or moderate stroke symptoms were more likely to have small, close-knit personal networks of immediate family and/or friends. Early arrivers, on the other hand, were more likely to have a more dispersed network of colleagues, friends and acquaintances.

These findings that slow arrivers have smaller, more closely-knit networks than fast arrivers confirmed a counterintuitive role of social environment in a medical emergency. Communication, the researchers concluded, was at the crux of the paradoxical findings. Others have made similar observations of early and late hospital arrival of patients experiencing chest pain.

“Closed networks are like echo chambers in which there is a tendency for everyone to agree to watch and wait,” said Dhand, the corresponding author of the stroke study. “People in large open networks negotiated less and were less likely to wait and see.”

To perform the study, Dhand and colleagues surveyed 175 patients within five days of suffering a stroke. Using self-reported information about personal social networks, the researchers created a personal network map for each patient (see illustration). The study focused on patients with milder symptoms, who are at higher risk for delay and were able to engage in the survey during hospitalization.

“Our communication analyses suggest this is because slow arrivers tend to contact strongly tied persons with whom they selectively disclose symptoms, over-negotiate plans, and reinforce a watch-and-wait strategy,” the authors wrote in Nature Communications in March 2019. “This is in contrast to fast arrivers who are more likely to contact or be surrounded by weakly tied individuals who act without negotiation.”

How Physicians Can Use Patients’ Personal Networks

The authors suggested that a shift from mass education about stroke symptoms to a more personal, targeted approach may help reduce delays. Stroke preparedness and outcome potentially could be improved by identifying at-risk patients who have small, close-knit networks and teaching them about stroke symptoms and communication pitfalls. The information also could help clinicians and patients work together to develop an action plan, which might include calling a designated friend.

For example, if a patient who is at risk of stroke has a very small, strongly bonded personal network, Dhand said, “that would warrant a discussion with the patient about how to how to disclose and communicate stroke symptoms in your social environment — and the importance of getting to the hospital on time.”

Help from an Online Tool to Identify Patients’ Social Networks

To help identify and assess patients’ social networks, Dhand and collaborators from around the country who work in population genetics and neurology have created an online tool to assess patients’ personal social networks. This prior work, which focused on patients with multiple sclerosis, could be used for other research and clinical work, Dhand said.

“We have an analysis pipeline that my group could help facilitate with other interested clinicians,” Dhand said. “We can create beautiful images of the patient’s social network that could go into clinical charts and provide quantitative tables of social network characteristics that can be used to aid in the clinician-patient decision making and discussions.”

Do Personal Networks Affect Stroke Recovery?

In other soon-to-be-published work that relates to social context and stroke, Dhand and colleagues found that patients with larger personal networks prior to an ischemic stroke reported better physical function in the six months after stroke, suggesting the significance of social networks in stroke recovery. They also found that personal networks became smaller and more close-knit after stroke, but those networks tended overall to include people with better health habits.

“There is a major effect of the people surrounding the patient that medicine typically ignores,” Dhand said. “Most doctors recognize the importance of the social support environment, but nobody has systematically mapped this environment.”