Immune-checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy has been a life-changing advance for a subset of people with cancer, but additional research is needed to learn how to make these treatments more broadly effective and longer lasting. A team led by scientists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital has published a paper revealing new details about the tumor characteristics that facilitate a strong clinical response to these drugs.

The presence of a factor called TCF in immune cells is currently believed to be a potential biomarker for predicting response to ICB. But the investigators found that this was not as neatly correlated with positive outcomes as previously believed and that additional tumor characteristics are also important. The research, done in mouse models of cancer, was published in Cancer Cell in September 2023.

“There’s been a lot of interest around using certain biomarkers for predicting ICB response,” says senior author Ana C. Anderson, PhD, of the Brigham’s Department of Neurology. “What we’ve shown here is that patients are not necessarily doomed to not respond if they have low levels of TCF1. Additionally, for those patients who do have low levels, there are ways that we can boost their response.”

Differences in Hot and Cold Tumors

Previous research from Anderson’s lab and other labs had shown that high levels of TCF1 in the CD8+ T cells present in a tumor were associated with a robust response to ICB, while low levels of TCF1 were linked to a poor response. Those studies were in line with clinical observations that seemed to show the same phenomenon.

“But what has come out since then is that the clinical data are not in full concordance,” Dr. Anderson says. “Depending on the type of cancer and the cohort of patients, the ability of TCF1 expression to serve as a biomarker for clinical response versus nonresponse to ICB is not always reproducible. We decided to look into this in more depth.”

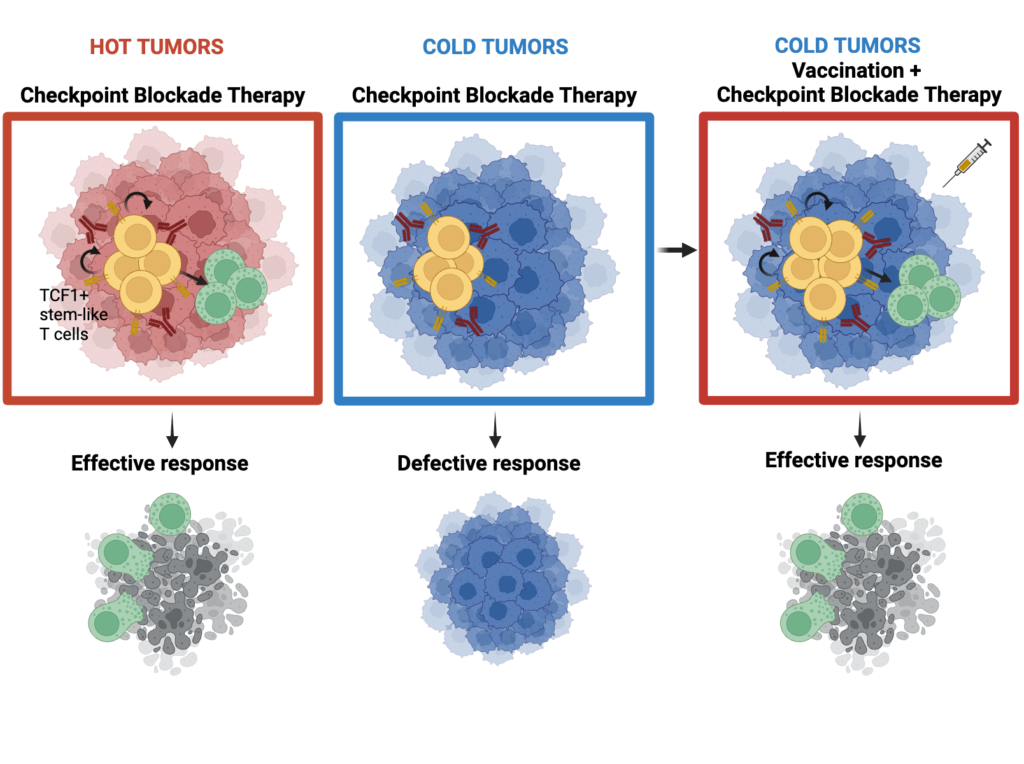

The investigators employed experimental mouse models of highly immunogenic (hot) tumors versus poorly immunogenic (cold) tumors. They found that in cold tumors, levels of TCF1 in the CD8+ T cells did indeed make a difference. In hot tumors, however, TCF1 was dispensable for predicting response to ICB; the hot tumors responded well regardless of their TCF1 levels.

“Cancers that can stimulate the immune system on their own do not automatically require a reservoir of TCF1-expressing cells,” says Giulia Escobar, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Brigham and first author of the Cancer Cell paper. Furthermore, certain forms of TCF1, which is known to have a lot of single-nucleotide polymorphisms, are also associated with susceptibility to autoimmune disease and, in similar fashion, could contribute to the diverse responses to ICB observed in people with cancer.

The next step was to look at whether it was possible to boost the ability of cold tumors with low levels of TCF1-expressing CD8+ T cells to respond to ICB. The investigators showed they could overcome that defect using a vaccine formulated with a peptide antigen. The findings suggest that such vaccines could one day be used in patients to increase the likelihood they would respond to ICB or to make responses more durable.

Translating Lab Findings Into the Clinical Setting

Based on these findings, Dr. Anderson believes certain cancers are more likely to respond to ICB whether TCF1 levels are low or high. That includes head and neck cancers caused by HPV. “Because these tumors contain antigens that are immunogenic, they are poised to better respond to checkpoint blockade irrespective of TCF1 levels,” she says.

This research is part of the broader focus of Dr. Anderson’s lab, which studies the function of different immune cell subsets in the tumor microenvironment. Other efforts focus on glioma and young-onset colorectal cancer.

“The ability to translate observations made in mouse models into patients is one of the powers of being at a large academic medical center like the Brigham, which has not just a clinical mission but also a strong research mission,” Dr. Anderson says. “Because the clinical mission is often at the forefront, it feeds into the research.”