Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center is world-renowned for its commitment to cutting-edge research. Over the years, its researchers have turned scientific discoveries into life-saving treatments, contributing to the development of 35 of 75 cancer drugs recently approved by the FDA for use in cancer patients.

One expanding area of neuro-oncology research at Dana-Farber Brigham focuses on glioblastoma, a highly invasive brain cancer with a less than 10% five-year survival rate. Cancer center physician-scientists are using genetically engineered oncolytic viruses that, when injected into a glioblastoma tumor, can initiate a direct attack against the tumor and stimulate the immune system to join in.

Ennio Antonio Chiocca, MD, PhD, is neurosurgeon-in-chief and chairman of the Department of Neurosurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Surgical Director, Center for Neuro-Oncology at Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center.

He has led a number of promising clinical trials to evaluate viral vector gene therapies and oncolytic viruses for brain cancer, including some of the first to combine these agents with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“Unlike other cancers, glioblastoma is defined as an immune desert,” he says. “Because glioblastoma tumors have few immune cells to attack them, we need to find a way to jumpstart the immune-system process without affecting normal brain cells.”

Building Specialized Viruses to Target Tumor Cells

Using DNA he creates in the lab, Dr. Chiocca and his team are building specialized recombinant herpes viruses that attack only glioblastoma tumor cells while sparing healthy brain cells. The viruses cause a molecular “red flag” to pop up on the surface of those cells, alerting the immune system to their presence. From there, the body’s own powerful defense system attacks and destroys the cancer in a matter of weeks.

“This virotherapy elicits a cellular immune response that ultimately leads to rejection of the glioblastoma cells in the central nervous system,” Dr. Chiocca says. “In a sense, the cancer has no way of knowing the virus is coming and doesn’t know how to defend itself once the virus is there.”

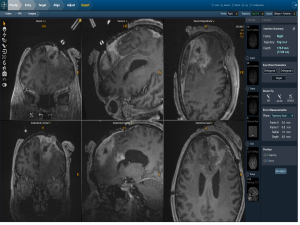

The virotherapy is delivered in situ (peritumorally after tumor resection or intratumorally via a stereotactic-guided catheter or convection-enhanced delivery). Two types of viral vectors are utilized: The first infect and do not replicate but still deliver an anticancer gene, while the second use replication-competent viruses that infect and replicate.

Serial Injections Show Promise

Dr. Chiocca’s oncolytic virus therapy has extended the lives of several glioblastoma patients, with others showing encouraging clinical outcomes. After a decade of development, the new treatment has finished a first human clinical trial and a second is soon to start.

Next, Dr. Chiocca is turning his attention to overcoming a major limitation in human glioblastoma science: the lack of serial interrogation of the tumor to determine if the therapeutic intervention is having the expected effect at a molecular level. He and his colleagues are designing a longitudinal trial to study this as part of the national, philanthropy-funded Break Through Cancer consortium.

“Studies to date have shown that repeated dosing and biopsies are fairly well-tolerated,” Dr. Chiocca says. “Moreover, because glioblastoma tumors have been shown to become infiltrated with an increasing number of effector T cells upon serial treatment, we may have a strategy for transforming glioblastoma’s immunological ‘cold’ microenvironment into one that is ‘hot’ and hopefully more recognizable for elimination by the immune system.”

Dana-Farber Brigham Tackles the Difficult Diseases Nobody Else Can

Dr. Chiocca points to the innovative spirit and translational-science focus at Dana-Farber Brigham, noting its well-deserved reputation for tackling the difficult diseases nobody else can address. He also praises the expertise of the nurses, operating room personnel, pharmacists, and other physicians for the regulatory and technical expertise they have honed while conducting oncolytic virus trials over the past 10 years.

“Not only are we engineering viruses to attack cancer directly, but we are also turning these viruses into delivery vehicles to carry other powerful cytotoxic agents,” he says. “This type of multipronged approach is needed for a cancer as devastating as glioblastoma, and here at Dana-Farber Brigham, we’re proud to be on the leading edge of discoveries that will lead to meaningful improvement in patient survival by the end of the decade.”