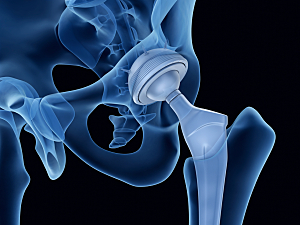

Clarifying abnormal spinopelvic mechanics can be critical to preoperative decisions about acetabular component positioning during total hip arthroplasty (THA) to reduce the risk of postoperative dislocation. The recently published Hip–Spine Classification suggests general targets for acetabular component positioning based on an individual patient’s spinal and pelvic alignment, and mobility.

This classification is elegant in its simplicity, but the recommended thresholds for alignment and flexibility are qualitative or, in some instances, nonspecific (i.e., “less than native anatomy”).

Researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital have created a quantitative tool that can be used for patient-specific preoperative planning and intraoperative adjustment of acetabular component position, with or without assistive intraoperative technology. Jeffrey K. Lange, MD, associate orthopedic surgeon in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Prem N. Ramkumar, MD, MBA, formerly a clinical fellow in the Department, and colleagues describe the development and validation of the online calculator in The Journal of Arthroplasty.

Development of the Tool

The researchers reviewed data on 2,437 consecutive primary THA procedures performed by five surgeons between January 12, 2014, and May 31, 2022. For each patient, three surgeons used the Hip–Spine Classification to classify the amount of spinal deformity and spinal stiffness.

The team derived an equation for spinopelvic biomechanics by establishing a unit vector projected from the center of the best-fit sphere to the acetabulum, then rotating that three-dimensional vector around the degrees of interest to establish a new unit vector. After starting angles were input, finishing angles were calculated for anteversion and inclination from the new unit vector.

Because this mathematical approach was so complex, the team created an open-source online calculator. The only preoperative measurements a surgeon needs to enter can be gathered from the physical exam (flexion contracture) or lateral X-rays (anterior pelvic plane, standing pelvic tilt or sacral slope, and sitting pelvic tilt or sacral slope). The surgeon also enters their goal for functional/standing inclination and anteversion.

Validation of the Tool

Twenty-two patients (0.9%) underwent a revision for instability. For each of them, the researchers compared the calculated patient-specific “safe-zone” target and the true position of the acetabular component on standing anteroposterior pelvis radiographs before and after revision. The following are the mean differences between the safe-zone targets and:

- The pre-revision acetabular component position—13.3° version and 9.1° inclination

- The post-revision acetabular component position—5.3° version and 3.2° inclination (P<0.01)

Thus, the average difference between stable and unstable acetabular components was only 8° version and approximately 6° inclination.

The research team also compared each patient-specific safe-zone target to the qualitative target recommended by the Hip–Spine Classification. the following are the mean differences between the safe-zone targets and:

- The medians of targets recommended by the Hip–Spine Classification—5.6° version and 2.2° inclination

- The extremes of targets recommended by the Hip–Spine Classification—7.9° version and 3.0° inclination

Commentary

The small differences between stable and unstable THA emphasize the sensitivity of component positioning. When comparing safe-zone targets to the median of Hip–Spine Classification targets, the 5.6° version difference may or may not be clinically significant. However, the 7.9° version difference between the safe-zone targets and the extremes of Hip–Spine Classification targets is nearly identical to the 8° version difference that distinguished stable from unstable THAs.

The patient-specific quantitative targets thus augment the Hip–Spine Classification to allow more nuanced preoperative planning.