Brigham and Women’s Hospital recently opened its innovative Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics. A joint clinical, research and education initiative, the new center brings together experts from neurology, psychiatry, neurosurgery and neuroradiology to develop innovative treatment methods for brain disorders that don’t respond to medication.

“This center was created to leverage what’s been a long-term initiative on the part of the Brigham: to develop unique approaches for taking care of brain diseases,” said Michael D. Fox, MD, PhD, director of the center. He is also the Raymond D. Adams Distinguished Chair in Neurology and the Kaye Family Director of Psychiatric Brain Stimulation.

A world-renowned investigator in brain imaging and brain stimulation, Dr. Fox recently joined the Brigham from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. He has published many studies on the identification of human brain circuits that underlie neuropsychiatric symptoms.

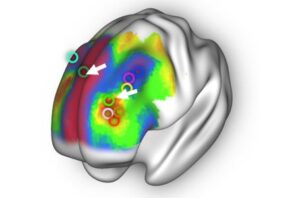

The Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics will provide treatments including deep-brain stimulation (DBS), focused ultrasound (FUS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Through its clinical trials program, the center will also seek to expand the applications for these therapies and study new treatment approaches. Translational research will be aimed at learning more about brain circuitry and lesion network mapping, among other investigations, to advance understanding of how the brain is wired and how that wiring could be targeted to treat different brain diseases.

In addition, the center will focus on training the next generation of leaders in neurology, psychiatry, neurosurgery and neuroradiology so that they can provide these therapies to patients.

Combining Circuit-Focused Treatments With Medication

Brain circuit-focused treatments work in a completely different way than medication. Rather than targeting chemical changes in the brain, they target specific anatomical brain regions or brain networks that are malfunctioning. The Brigham is a leader in many of these approaches, including MRI-guided FUS, which can noninvasively treat tissues deep in the brain. Furthermore, thanks to its advanced MRI technologies, the Brigham offers asleep DBS within an MRI scanner in addition to traditional awake DBS.

“Medication is still the first approach for almost all neurologic and psychiatric symptoms, but these symptoms can become refractory over time, or may not respond at all,” Dr. Fox said. “Patients who don’t respond to medication are ideal for referral to this center.”

Dr. Fox estimated that only one in five Parkinson’s patients who could benefit from DBS currently are referred for this therapy, even though studies show many of these patients do better after receiving it. He said that part of the problem may be a lack of understanding among other medical professionals about how much these therapies can improve outcomes.

“When someone comes to us for treatment, we work as a team with the neurologist or psychiatrist who referred them,” Dr. Fox explained. “The treatments we offer are not a replacement for medical therapy, and communication between our team and the patient’s other doctors is very important for successful treatment.”

Making TMS Treatments More Precise

Shan H. Siddiqi, MD, a neuropsychiatrist and director of psychiatric neuromodulation research for the center, is leading much of the research on TMS. He is currently leading a clinical trial looking at whether the treatment can be modulated to more specifically treat depression versus anxiety based on which circuit in the brain is being targeted with the magnetic stimulation.

“In the past, TMS has been aimed based on scalp landmarks,” he said. “We now know that imaging can help to determine whether we can more precisely target this therapy to choose the right target for the right patient.”

Dr. Siddiqi noted that besides providing better treatment for patients who don’t respond to medication, TMS may also be preferred in some cases because it has milder side effects. But he pointed out that insurance usually does not cover TMS unless patients have tried antidepressant medications.

The large amounts of data generated by research into brain circuits, including pinpointing specific areas to make treatment more personalized, require computational approaches. “The purpose of the Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics more broadly is to break down all this research and data to find better real-world treatment targets that we can influence with these various approaches,” Dr. Siddiqi said.

“This initiative involves people from many different areas across the Brigham, including some of the best neurosurgeons, psychiatrists and other experts anywhere in the country,” Dr. Fox concluded. “It is the strength of this collection of individuals that makes this program so exciting.”