An intranasal vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is expected to begin its first human trial in 2020, culminating nearly 25 years of research led by Howard L. Weiner, MD, co-director of the Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

The vaccine uses the immune modulator Protollin to activate monocytes in the cervical lymph nodes that migrate to the brain and trigger macrophage clearance of beta amyloid plaques, but without creating or infusing beta amyloid antibodies. Manufacturing of the vaccine is now underway, and a dosing trial of the immunotherapy is planned for a small group of patients with mild Alzheimer’s.

Though Dr. Weiner cautioned against premature hope in fully translating the work from animal studies, he described the potential: “If this works, it could be a nontoxic treatment for people with Alzheimer’s, and it could also be given early to help prevent Alzheimer’s in people at risk.”

The vaccine is one thrust among Dr. Weiner’s longstanding and pioneering work in harnessing the immune system, particularly the mucosal immune system, to treat autoimmune, neurologic and other diseases. His groundbreaking work in cyclophosphamide ushered in multiple sclerosis treatments that dampen the overactive immune response that characterizes that disease.

An Immunological Approach to Alzheimer’s Disease

Extending this expertise to Alzheimer’s disease, Weiner saw possibilities for a reverse approach – that is, to activate an immune response against the buildup of beta amyloid protein plaques and subsequent tau tangles that cause memory loss. Starting in the mid-1990s, he and others began treating transgenic mice with A-beta protein to create an immune response against A-beta.

To enhance the immune response to the amyloid, Weiner and his team homed in on Protollin, a nasal proteosome-based adjuvant that had been used safely in humans as an adjuvant for other vaccines.

Vaccine’s 25-Year Journey to Human Trials

To activate the immune system without incurring encephalitis, as had occurred in other investigators’ trials of more conventional amyloid protein-based vaccines, the team eventually turned to Protollin alone without infusing or causing development of anti-amyloid antibodies.

This novel antibody-independent approach sidesteps potential toxicity. “Where others have triggered antibody creation by amyloid vaccination or artificially put anti-amyloid antibodies into the patient intravenously, what we’re doing is stimulating the immune system in a natural way not only to clear the beta-amyloid, but also to address other abnormalities in the brain,” said Weiner.

Three key papers charted the course to the vaccine that is now being manufactured:

- A 2005 paper showed that nasal vaccination with an immune modulator used in MS (glatiramer acetate) plus Protollin cleared B-amyloid in a mouse model of AD. There were no toxic side effects or evidence of encephalitis.

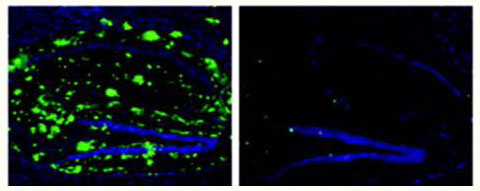

- A 2008 paper added evidence that using Protollin alone without antibody creation could activate microglia in young mice (which was associated with decreased beta-amyloid) and that older mice treated with Protollin showed decreased beta-amyloid and improved memory function.

- A third mouse study, published in 2012 provided more support for the potential use of Protollin as a macrophage immunomodulator to reduce cerebrovascular amyloid, prevent local brain microhemorrhages and improve cognition.

In 2012-13, Dr. Weiner’s team won a NIH Transformational grant to pursue work on the “Role of the Innate Immune System in Aging and Development of Alzheimer’s Disease.” In this further work toward a human vaccine, Weiner turned to his longtime research partner Dennis J. Selkoe, MD, co-director of the Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases and an expert in the biology of Alzheimer’s and amyloid proteins.

From Mice to Humans

In the upcoming SAD (single ascending dose) trial, Selkoe recently explained, success would be defined as blood biomarker evidence of activated mononuclear cells and enhanced beta-amyloid phagocytosis, with no obvious negative effect. If this is evident in the first dozen patients or so, a second cohort would receive repeated doses at two-week intervals. “That is how we imagine its ultimate use,” he added.

While there has been significant public attention to disappointing clinical trials of therapies aimed at stopping AD progression, Selkoe has noted that the recent positive results of a trial of an anti-Aβ antibody (aducanumab) was highly encouraging. Selectively boosting immune responses early in the course of the disease may be able to slow or stop progression before tau protein build-up and its related cognitive problems develop, Weiner said.

Beyond Alzheimer’s Disease

A book author and filmmaker, Weiner has written and directed a documentary (“What Is Life”) and a feature film (“Abe & Phil’s Last Poker Game”) — creatively fulfilling endeavors that he has balanced with ongoing research.

He continues to direct the Partners Multiple Sclerosis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which he established nearly two decades ago as the first integrated multiple sclerosis center to bring together clinical evaluation, MRI imaging and immune monitoring.

In more recent years, in addition to pursuing the nasal Alzheimer’s vaccine, his lab’s work on immunotherapy in neuro-oncology has served as a foundation for commercial development of therapeutics for cancer, fibrosis and autoimmune disease.

“This work is extraordinarily satisfying,” Weiner said. “The immune system plays a very important role in all neurologic diseases. And it’s exciting that after 20 years of work in animals, we can finally test Protollin and other experimental vaccines in people.”

Weiner expects the Alzheimer’s intranasal vaccine trial (Protollin) to begin in the fall of 2020, pending review by the FDA.

*Image adapted from Annals of Neurology, First published: 14 May 2008, DOI: 10.1002/ana.21340