Image courtesy of INSIGHTEC

Each week, two or three patients with medically refractive essential tremor undergo MRI-Guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) Thalamotomy at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, with often-life-changing results – fulfilling the promise of a technology that dawned here 20 years ago.

“We very accurately and precisely ablate the specific nucleus in the thalamus to dramatically reduce tremor,” said G. Rees Cosgrove, MD, FRCSC, a stereotactic and functional neurosurgeon and Director of Epilepsy and Functional Neurosurgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, one of only 11 MRgFUS treatment centers in the United States and the only one in New England. “We’re learning more and more that this novel technology can deliver the focused ultrasonic energy exactly where we direct it to.”

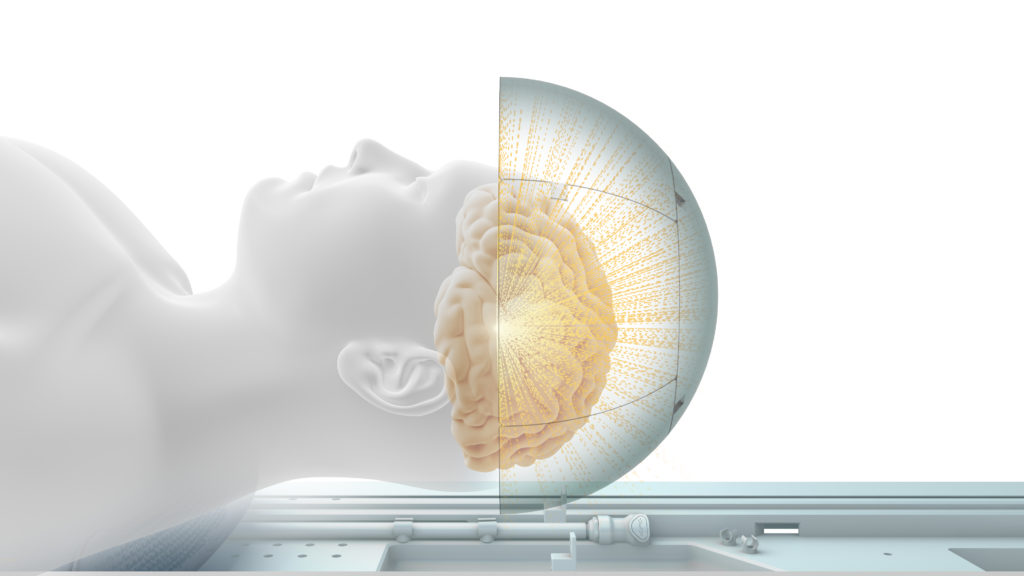

Early work in MRI-guided surgery and focused ultrasound at Brigham and Women’s was a foundation for this noninvasive treatment. A trio of physicians and scientists, with high hopes for using ultrasound in the brain, teamed up with Israeli engineers who eventually created the novel treatment helmet, containing approximately 1,000 tiny ultrasonic emitters that make the procedure possible.

With essential tremor, the world’s most common movement disorder, abnormal activity in the brain’s motor circuitry results in superimposed shaking, usually of a limb. This inherited condition affects approximately seven million Americans. The frequency and severity of essential tremor increases over age 65. The tremor can become debilitating as individuals struggle to write, cook, eat in public and face other challenges of daily living.

For patients whose tremor is refractive to pharmacotherapy (typically propranolol or primidone), the surgical option historically has been unilateral radiofrequency thalamotomy — open surgery to destroy a small portion of the thalamus. In the past two decades, this older procedure has been supplanted by deep-brain stimulation (DBS), in which electrodes are permanently implanted in the thalamus and attached to an impulse generator under the skin of the chest to block the tremor-causing activity.

MRgFUS can provide unilateral relief non-invasively, without the programming and battery changes needed for DBS, Cosgrove notes. “It’s still surgery, but without the standard surgical risks of bleeding, infection, and recovery from the injury of surgery.”

At Brigham and Women’s, MRgFUS is typically a 3-hour outpatient procedure. A pre-treatment MRI maps the anatomy. A CT scan gauges skull thickness, which excludes some patients. For patients who qualify, the CT helps determine the ultrasound strength required from specific angles.

Before treatment, patients are fitted with a frame that mates with the spherical treatment helmet. The patient lies awake on the treatment bed in the MRI scanner while the emitters direct sound waves at the predetermined point in the thalamus. With physician monitoring, the temperature rises enough to ablate the targeted area.

The patient moves in and out of the MRI between applications to perform spiral-drawing and other tasks used to evaluate the effect of the ablation. Results are visible in real time.

“We actually see an abolition of the tremor of the hand while we’re doing the treatment,” said Cosgrove. “Patients look at their hand that has been shaking for years and years, and now it’s still. And they can move it exactly how they want to. A big smile comes over their face. That’s a pretty remarkable achievement.”

Cosgrove, a past president of the American Society of Functional and Stereotactic Neurosurgery, has performed more than 500 operations in patients with intractable movement disorders, including thalamotomy, pallidotomy, DBS and other neuromodulation procedures. He participated in investigative phases of the MRgFUS for essential tremor, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2016, the same year the device received FDA approval. At Brigham and Women’s, Cosgrove is guiding trainees in the procedure.

Follow-up data, up to 3 to 4 years after the procedure, shows enduring effects in reducing tremor, with no delayed side effects, said Cosgrove, adding, “The effects on the quality of life in patients is so dramatic.”

To continue refining the treatment, he and others are using the pre-treatment MRI to visualize white matter connections and explore ways of targeting and changing the brain circuitry even more precisely.

MRgFUS also is being investigated for treating Parkinson’s disease and other neurological diseases; Brigham and Women’s work on a safety trial has been completed and an efficacy trial is underway. Other indications are being considered for research.

“This is the most revolutionary advance I’ve seen in all my years performing movement disorder surgery,” said Cosgrove. “We are standing on the threshold of discovering what this new technology will do in the future.”

In the early 2020, Brigham and Women’s Hospital became the first site in the United States to treat 100 patients (outside of a clinical trial) with FUS.