Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystem autoimmune disease that predominantly affects women. Early treatment improves symptom management and prevents joint and organ damage. Thus, identifying those at high risk of developing SLE could significantly enhance patient outcomes.

Although several genetic and environmental risk factors for SLE have been established, there are no accurate risk prediction models. It’s a topic that has bewildered rheumatologist Karen Costenbader, MD, MPH, director of the Lupus Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, since medical school.

“Why do some people get this complex autoimmune disease, while others do not?” she says. “We know that genetics are somewhat predictive, but there are many other risk factors that subtly or not so subtly affect one’s risk of developing lupus or a related autoimmune disease over a lifetime.”

Dr. Costenbader is the senior author of a paper published in Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism that presents the first SLE risk prediction model to incorporate known genetic, environmental, and lifestyle risk factors, as well as family history. Clinicians one day may be able to use the model to classify future SLE risk in at-risk patients and accelerate interventions.

Genetics Are Only Part of the Story

Utilizing data from the first two Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) cohorts and the Black Women’s Health Study, Dr. Costenbader and her team have uncovered a wide range of factors related to increased SLE risk among women, including:

- Reproductive and hormonal factors, such as early-age menarche, use of oral contraceptives, and postmenopausal hormones

- Psychosocial factors, such as depression, child abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and decreased sleep

- Cigarette smoking

- Obesity

In the NHS cohorts, study participants provided self-reported prospective data on lifestyle, behavioral factors, and disease outcomes—including new diagnoses of SLE. About a quarter of the women in each of the two cohorts also donated blood samples for genotyping.

Dr. Costenbader and her colleagues identified and matched 138 women who developed incident SLE to 1,136 women who did not. In assessing for SLE risk, the team considered the risk factors outlined above, as well as race/ethnicity, income level, and geographic region of residence. They also used genome-wide genotyping results to calculate an SLE-weighted genetic risk score (wGRS).

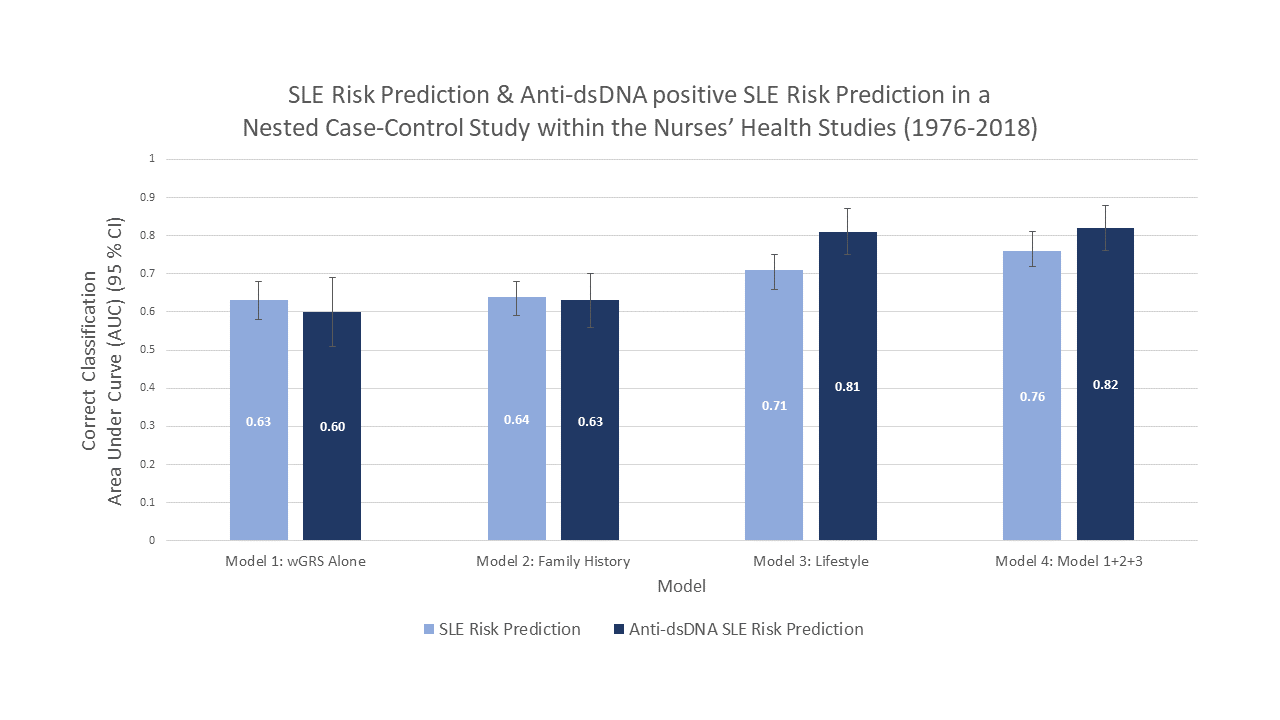

The team subsequently developed four sequential models to predict SLE risk among women:

- wGRS

- SLE/rheumatoid arthritis family history alone

- The selected lifestyle, reproductive, and environmental factors above

- A combination of the first three models

The fourth model—based on genetics, family history, and eight lifestyle and environmental factors—showed the best discrimination, with an optimism-corrected area under the curve of 0.75. They repeated their statistical modeling for predicting risk of anti-dsDNA+ SLE, a subtype of SLE associated with more severe disease and kidney involvement, and the area under the curve for risk prediction was even a bit better.

“What we found is that genetics by itself doesn’t explain a lot of the risk for SLE,” Dr. Costenbader says. “You can bump up the curve and more correctly predict risk by also considering these other factors.”

What the Future Might Hold

Noting that the NHS cohorts include mostly women of European descent with an average age of SLE onset of approximately 52 years, Dr. Costenbader says further research is needed in more diverse, younger cohorts. She would also like to see much more progress in understanding the biologic mechanisms associated with SLE risk.

“It would be exciting if we could get our risk prediction models to the point where they are good enough to screen people,” Dr. Costenbader says. “We do that for cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and many other diseases. If you have genetics as well as risk factors, and you could predict someone’s 10-year risk of developing SLE as ‘x percent,’ for example, then you could really screen the population for who needs interventions and who does not.”

The prospect of early intervention prior to onset of symptoms—especially with people who have a family history of SLE and/or are in a high-risk demographic—is particularly tantalizing to Dr. Costenbader. African American and Hispanic women, who are disproportionately affected by SLE, are two obvious groups who stand to benefit.

“I would love to see population-based screening using a combination of genetics and all these other factors to risk-stratify people and see who might be interested in interventions,” Dr. Costenbader says. “By screening a very high-risk population, we might be able to recommend impactful lifestyle modifications or even use an early treatment if people were at high enough risk. That’s where I’d like this research to go in the future.”