Multiple studies have linked higher aldosterone levels with higher levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) in individuals without primary hyperparathyroidism (P-HPT), where there is no autonomous PTH production or neoplasia. In those individuals, acutely stimulating aldosterone production increases PTH secretion; conversely, treatments to medically or surgically lower aldosterone decrease PTH secretion.

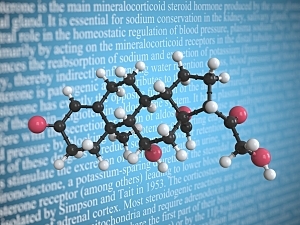

Several uncontrolled studies have suggested inhibiting or lowering aldosterone production may decrease PTH secretion. The only randomized, controlled study of the issue, the EPATH trial, assessed the efficacy of aldosterone antagonism with fixed‐dose eplerenone, a mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonist, versus placebo in patients with P‐HPT.

The results demonstrated no meaningful reductions in PTH or calcium, compared with placebo, despite reductions in blood pressure. However, the study had an important limitation: nearly half of the participants were also taking renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, which may have blunted the influence of eplerenone.

Wasita W. Parksook, MD, MSc, a research fellow in the Center for Adrenal Disorders at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Anand Vaidya, MD, MMSc, director of the Center, and colleagues recently completed a similar trial in patients with P-HPT who were off RAAS inhibitors. They report in Clinical Endocrinology that neither eplerenone nor amiloride (an active comparator) decreased PTH or calcium levels compared with placebo.

Methods

In the new trial, 41 patients from the Mass General Brigham network who had P‐HPT were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to receive eplerenone, amiloride, or placebo for four weeks. Eplerenone is a potassium-sparing diuretic that blocks the action of aldosterone at the MR. Amiloride is a potassium‐sparing diuretic similar to eplerenone in that it can blunt the action of aldosterone in the distal nephron, but instead of targeting the MR, it inhibits epithelial sodium channels.

All participants stopped angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, sodium channel inhibitors, and MR antagonists two weeks before starting the study protocol.

Patients and clinicians were blinded to the medication, but clinicians chose the initial capsule dose and guided subsequent titrations. The initial doses were eplerenone 12.5 to 25 mg twice daily or amiloride 1.25 to 2.5 mg twice daily, dictated by the participant’s baseline blood pressure and clinician discretion about the risk of hypotension, or placebo.

After two weeks, the study medication was increased (if considered possible without causing hypotension or hyperkalemia) to maximum doses of eplerenone 50 mg twice daily or amiloride 5 mg twice daily.

Results

36 participants had serum PTH and calcium measured before and after the four‐week treatment. All had eplerenone or amiloride titrated to the maximally tolerated dose.

Both medications induced the expected decreases in blood pressure, increases in renin activity, increases in aldosterone concentrations, and trends toward increases in serum potassium, compared with placebo. However, neither eplerenone nor amiloride lowered circulating PTH or calcium levels compared with placebo.

There were no serious or unexpected adverse events.

Implications for Practice

The mechanistic role of aldosterone and MR in P‐HPT pathophysiology may be clinically irrelevant. Taken together, this study and the EPATH study provide robust evidence that MR antagonists (and possibly any potassium‐sparing diuretic) have no appreciable clinical role in treating P‐HPT.