PARP inhibitors have become an important part of the arsenal for treating cancers caused by BRCA mutations — including breast cancer. Recently, clinical trials have begun looking at the combination of PARP inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors in breast cancer, with the goal of making treatment more effective and longer lasting.

Now research led by scientists from Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center has found that adding another class of therapies — drugs that target tumor-associated macrophages — may also boost the ability of PARP inhibitors to bring these tumors under control. This work, done in models of breast cancer in mice, was published in December 2020 in Nature Cancer.

“PARP inhibitors offer many patients the opportunity for great antitumor responses,” said Jennifer Guerriero, PhD, lead investigator for breast surgery at the Brigham, director of the Dana-Farber Breast Tumor Immunology Laboratory and senior author of the paper. “But most patients eventually relapse, and unfortunately there aren’t many options at that point. One of the goals of this work is to find ways to overcome resistance to PARP inhibitors.”

Targeting a Natural Repair Mechanism

Efforts in this area are possible thanks in part to funding from a National Institutes of Health’s Specialized Program of Research Excellence grant. “We’ve focused quite a bit on trying to understand the immune mechanisms that might enhance responses to PARP inhibitors,” Dr. Guerriero said.

A study published in Cancer Discovery in 2019 by Dr. Guerriero and Geoffrey Shapiro, MD, PhD, director of Dana-Farber’s Early Drug Development Center and clinical director of Dana-Farber’s Center for DNA Damage and Repair, found that one way PARP inhibitors work is by activating programs that lead to the recruitment of CD8+ T cells. The latest efforts further built on the approach of enlisting the immune system to make PARP inhibitors more effective.

The major focus of Dr. Guerriero’s lab is the role of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. “The job of the macrophage is to repair damaged tissue,” she said. “When they get to a tumor and sense that there’s no oxygen, they get to work repairing the tumor. Of course, this is not good for the patient.”

In the new study, investigators added a drug to target this behavior: Along with the PARP inhibitor olaparib, the animals were given antibodies to macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R). The animals used in the trial were a mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer with a mutation in BRCA1.

Drug Combinations Show Promise for New Treatments

In the paper, the researchers reported that the antibodies significantly enhanced both innate and adaptive antitumor immunity and extended survival in the mice. Further investigation revealed that CD8+ T cells mediated this effect.

“In partnership with clinicians in the Breast Oncology Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, we are working to move this combination into the clinic,” Dr. Guerriero said.

The drug that targets CSF1R, pexidartinib, has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of tenosynovial giant cell tumor but has shown limited efficacy for other types of cancer. “We know that it’s well-tolerated and safe,” Dr. Guerriero continued, adding that she believes its efficacy has been limited so far because it has not been tested in this sort of combination.

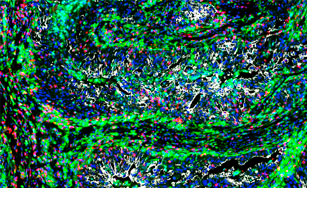

Dr. Guerriero credited many of her colleagues for assisting in this research, including Dr. Shapiro; first author Anita Mehta, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in her lab; and Elizabeth Ann Mittendorf, MD, PhD, a breast surgeon at the Brigham. Imaging of the tissue samples was enabled thanks to technology developed by Peter Sorger, PhD, of Harvard Medical School. Dr. Guerriero explained that strong working relationships across the cancer center have helped bring together expertise in lab research, clinical care, and imaging technology.

“This work was possible because of this wonderful collaboration,” she concluded. “It took multiple hands to help push this research forward.”