A preliminary trial of focused ultrasound (FUS) to open the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in patients with glioblastoma (GBM) is underway at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and two other sites. One of the study’s first patients, treated by neurosurgeon Alexandra J. Golby, MD, has shown that the barrier was breached safely and successfully.

The study is a first step toward using non-invasive FUS technology to deliver chemotherapy more effectively to the site of a brain tumor at concentrations higher than occurs with current treatments.

“Our ultimate goal is to be able to get more drug into the tumor and therefore have more efficacy than the current standard of care in preventing recurrence,” said Golby, director of image-guided neurosurgery in the Department of Neurosurgery. “But first we have to see if it’s feasible to open the blood-brain barrier safely, repeatedly and reversibly.”

The small, multi-site study is testing whether FUS can temporarily open the BBB in glioblastoma patients undergoing standard chemotherapy treatment. Golby and co-investigators at the University of Maryland and the University of Virginia are seeking to determine whether it is possible to create a window for GBM treatment by opening the BBB.

How Focused Ultrasound Disrupts the Blood-Brain Barrier

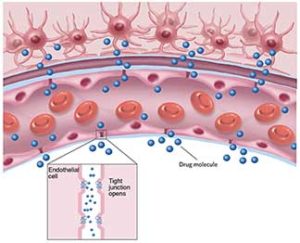

The BBB, a protective layer of tightly joined cells within the brain’s capillaries, provides the evolutionary benefit of preventing toxins and infectious agents from entering the brain. But it also limits the amount of medication that can reach diseased targets to treat brain tumors, Alzheimer’s disease and other neurologic conditions.

To address this problem, Golby and others are turning to MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS), an approach that is rooted in work that began at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and is now used for a handful of neurosurgical applications.

In animal studies, focused ultrasound has been shown to disrupt the BBB. The likely cause is cavitation (oscillating microbubbles that form as a mechanical effect of the ultrasound waves), which exerts pressure on endothelium of brain capillaries and temporarily forces apart the tight junctions of the BBB.

Early efforts showed that the high energy needed to induce cavitation also caused side effects. But more recently, researchers found that injecting pre-formed bubbles before FUS treatment reduced the energy required and, in turn, resulted in less unintended tissue damage.

The study underway is the first in the United States to test opening the BBB in resected glioblastoma patients for potential delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to the tumor site.

Targeting the Site of Likely GBM Recurrence

Study inclusion criteria require that patients have a Grade IV glioma (glioblastoma) and be eligible for adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) treatment. After being treated with the standard of care for newly diagnosed GBM — resection, radiotherapy and TMZ — patients are scheduled for FUS, which is performed immediately prior to each monthly cycle of chemotherapy.

The half-day treatment requires affixing a treatment helmet that contains more than 1,000 tiny ultrasonic emitters that are preprogrammed via MRI guidance to focus ultrasound waves precisely on the periphery of the tumor resection cavity. Before sonication, the patient receives intravenous administration of microbubbles. After sonification, gadolinium is given to image where the BBB disruption has occurred. TMZ is given within two hours following the FUS procedure.

“We are targeting parts of the tumor that don’t enhance until we do the BBB opening,” said Golby. The disruptive effect on the BBB persists for a period of hours immediately after treatment.

This early trial is limited to non-eloquent brain regions, but the researchers expect to expand the work eventually to patients with lesions in eloquent areas.

Dr. Golby’s patient, who has had three courses of FUS, is the third in the study to receive treatments. Two other patients also began in late 2019, under the direction of the study’s principal investigator Graeme Woodworth, MD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Results of the first five patients in this industry-sponsored study will undergo an interim analysis by the FDA before enrollment of the full 20 patients in the study protocol.

Long History of Success with Focused Ultrasound at Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Much of the initial work in image-guided FUS for noninvasive applications in the brain began at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in the 1980s. A trio of physicians and scientists teamed up with Israeli engineers who eventually created a novel treatment helmet, containing the tiny ultrasonic emitters that make the procedure possible.

As the technology became commercially available, it gained traction as an effective and minimally invasive treatment of neurologic conditions, most notably for essential tremor. At Brigham and Women’s, the procedure is done under the direction of neurosurgeon G. Rees Cosgrove, MD, FRCSC, who was involved in its investigative phases. Years later, in early 2020, Brigham and Women’s Hospital became the first site in the United States to treat 100 patients with FUS outside of a clinical trial.

For essential tremor, the ultrasonic beams are focused to precisely and accurately ablate the specific nucleus in the thalamus that is causing the tremor. For GBM, much lower energies are used over a larger area to disrupt the BBB and facilitate drug delivery.

Addressing the Needs of Glioblastoma Patients with Few Options

For this initial safety and feasibility study of breaching the BBB, Golby and the other investigators are evaluating and classifying any adverse events related to the BBB disruption.

The study protocol calls for repeating the FUS procedure during six cycles of chemotherapy for each patient. Learning whether the BBB can be opened repeatedly is essential because of the multiple doses of chemotherapy required for treatment, Golby noted. Feasibility of repeated BBB disruption is being evaluated via post-procedure MRI to determine whether gadolinium reaches the brain. Reversibility of opening the BBB is also important to ensure that the brain is not left vulnerable to infections and toxins.

If the study is successful, subsequent studies would be needed to determine whether the chemotherapy agent itself enters the brain and whether patients who undergo FUS with chemotherapy subsequently have fewer recurrences and live longer.

For now, though, investigating ways to breach the BBB to treat glioblastoma may open avenues for patients who have few options.

“For today’s patients, one challenge is that most clinical trials are for recurrence. There are very few trials offered to newly diagnosed patients,” Golby said. “This is a way to address a desperate population.”

Eventually, the approach may provide a means to deliver therapeutic molecules to focally address other neurologic disorders. If successful, Golby added, “treatment through the blood-brain barrier potentially can be used for many other conditions.”