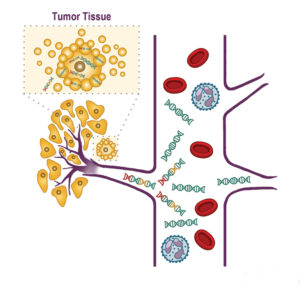

Image: Some tumors can shed free-floating DNA into the blood. Emerging technologies have the potential to detect these abnormal DNA signals, laying the groundwork for a blood test which could be used for cancer detection.

Image: Some tumors can shed free-floating DNA into the blood. Emerging technologies have the potential to detect these abnormal DNA signals, laying the groundwork for a blood test which could be used for cancer detection.

As next-generation genomic sequencing has become faster and more affordable, a significant aim in cancer research has been the development of so-called liquid biopsies. Those blood tests, some of which are now being evaluated in clinical trials, are used in people who already are known to have cancer. They aim to uncover specific driver mutations that can match tumors with a particular targeted therapy while also enabling patients to avoid more-invasive types of biopsies.

A Blood Test That Analyzes Cell-Free DNA

The quest for a blood test that could be employed for cancer detection—rather than for analyzing a cancer that has already been identified—has been less successful thus far. But at the 2019 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual meeting in September, an international team of investigators presented results from a blood test in development that could be used to screen for over 20 types of cancer in the blood.

The study was led by Geoffrey R. Oxnard, MD, a medical oncologist at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center. The assay was developed by the biotechnology company Grail.

“Tests that look at cell-free DNA in the blood have become quite common in maternal-fetal medicine,” Dr. Oxnard said. “Our aim is to develop a blood test that can collect DNA from a cancer patient or a person at risk of cancer and look for the hallmarks of cancer.”

In the study reported at ESMO, almost 3,600 blood samples were analyzed. The researchers analyzed cell-free DNA from 1,530 people who were known to have cancer and 2,053 people without cancer. The cancers in the study included many of the most common types, such as breast, colorectal, lung, prostate and pancreatic.

The team reported that the specificity of the test was 99.4 percent. The average sensitivity of the test was 76 percent across a pre-specified cohort of 14 cancer types; sensitivity was higher for more advanced cancers. Among cases with a cancer signal detected, the assay identified the correct type of cancer 89 percent of the time.

Looking for Methylation Signatures

Unlike many other cancer blood tests that are in development, the Grail test looks at DNA methylation rather than gene sequence mutations or changes in copy number. Dr. Oxnard previously reported the initial results of Circulating Cancer Genome Atlas (CCGA) study, which aimed to identify the best way to detect a cancer signal in the blood. “This type of test needs to be sensitive for a wide range of cancers,” he said. “It also needs to be specific and accurate.”

The CCGA project, which enrolled more than 15,000 individuals, was first presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in June 2018. In this initial analysis of 2,800 participants, investigators found that looking for methylation signatures was the best option for cancer detection because it avoids mutations that may be present due to clonal hematopoiesis. Dr. Oxnard said looking for methylation signatures is also the best way to distinguish cancer type because each cancer has its own signature.

Much more research is needed before such a screening test can become a regular part of clinical practice, Dr. Oxnard noted. An important next step is to determine how to make the test more scalable. Ongoing clinical validation efforts are focusing in part on people already going for other cancer screenings, such as mammographs and low-dose CT lung scans.

“There’s a long road ahead, but there is certainly an urgent need,” he said. “In looking at the results that we’ve seen so far, it’s very clear what the potential is. We’re working as quickly as possible to move this forward and scale it up.”