Andrea L. Roberts, PhD, Susan Malspeis, MS, Laura D. Kubzansky, PhD, Candace H. Feldman, MD, Shun-Chiao Chang, ScD, Karestan C. Koenen, PhD, Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH Arthritis & Rheumatology, 2017;69(11):2162-2169.

Andrea L. Roberts, PhD, Susan Malspeis, MS, Laura D. Kubzansky, PhD, Candace H. Feldman, MD, Shun-Chiao Chang, ScD, Karestan C. Koenen, PhD, Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH Arthritis & Rheumatology, 2017;69(11):2162-2169.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an enigmatic inflammatory autoimmune disease. A widely-accepted etiologic model for SLE is that environmental exposures “trigger” the disease in genetically-predisposed individuals. The epidemiology of SLE – 80-90% of cases occur in women, and disease severity is much greater in African-American and non-white populations – points to the obvious role of genetics, and genome-wide association studies have identified many genetic factors associated with SLE susceptibility. Meanwhile, there is a growing list of exposures which have also been associated with SLE risk in epidemiologic studies, which include current cigarette smoking, crystalline silica, pesticides, and oral contraceptives and postmenopausal hormones among women. Models for how these and other environmental exposures may contribute to autoimmune disease pathogenesis include elevating concentrations of systemic inflammatory cytokines, increasing oxidative stress, and impairing T-cell function.

The Nurses’ Health Study cohorts, begun at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Channing Laboratory over 40 years ago, provide a rich source of data on exposures that could be associated with risk of SLE. Dr. Karen Costenbader and colleagues examined whether experiences of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were related to future risk of developing SLE among women. They hypothesized that women who experienced trauma or had PTSD were more likely to develop SLE. Past studies demonstrate that people with SLE experience much more distress and anxiety than healthy individuals, but it has not been clear from these cross-sectional studies whether these symptoms were the consequence of SLE or whether they could in fact risk for develop SLE. Exposure to traumatic events and PTSD have been associated with increased risks of developing other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis. Prior studies were performed mainly in populations of war veterans, with relatively high prevalence of PTSD, in which women are underrepresented.

Costenbader and colleagues analyzed information on 54,763 U.S. women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study II, which started in 1989, with 24 years of follow-up. Self-reports of new onset doctor-diagnosed SLE have been validated in a two-stage process that includes a screening questionnaire for signs and symptoms of SLE, followed by medical records release and review by two rheumatologists to confirm SLE if the questionnaire is positive. PTSD and trauma exposure were assessed using state of the art questionnaires. All participants were asked to report whether they had had any of 17 past stressful or traumatic events, including child abuse, physical assault, and serious accidents, and, if so, how old they were at the time. Women also were asked whether they had symptoms indicative of PTSD following these events. Among the women who were asked about PTSD, 73 new cases of SLE were identified. Researchers then examined whether there was an association between trauma and PTSD in the past and the new onset of SLE during the study. They also investigated whether higher rates of cigarette smoking, oral contraceptive use, and obesity among women with trauma and PTSD could account for their possible higher risk of developing new SLE.

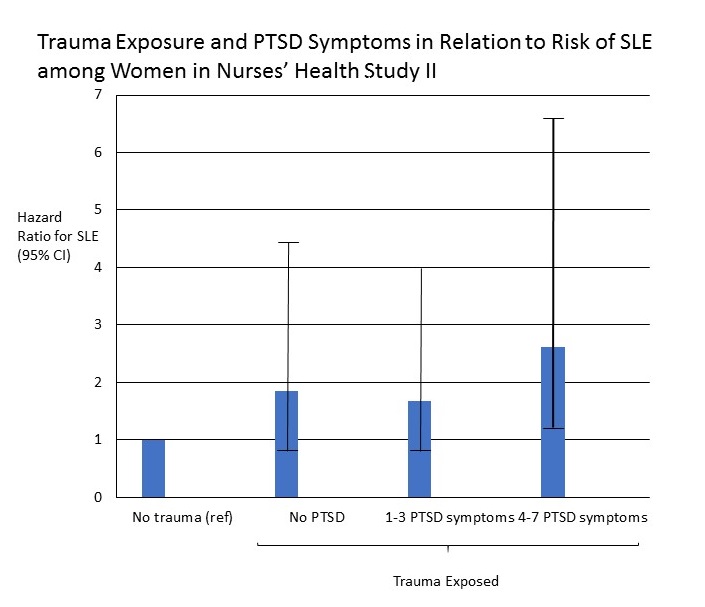

In models adjusted for race and age, a high number of PTSD symptoms was associated with an almost three-fold increased SLE risk compared to an absence of history of trauma or PTSD (hazard ratio 2.94, 95% confidence interval 1.19, 7.26). Although smoking, oral contraceptive use, and obesity were more common in women with trauma and PTSD, they accounted for only a small part of the higher risk of SLE in these women. Women who reported past trauma, with or without subsequent PTSD, were also at increased risk of developing SLE (fully-adjusted hazard ratio 2.61, 95% confidence interval 1.19, 5.73). A dose-effect was seen with PTSD severity: with increasing number of PTSD symptoms reported, the risk of developing SLE also increased.

This prospective cohort study among civilian women in the U.S. contributes to growing evidence that psychological trauma may affect the immune system, increasing risk of developing autoimmune disease. The magnitude of the increased risk of SLE associated with past trauma and PTSD was large, and in this study, were both more strongly related to developing SLE than was smoking Persons exposed to trauma or have symptoms of PTSD need appropriate treatment, but it whether the increased risk of SLE is potentially reducible with such therapy is not known.